When Aaron Swartz committed suicide in 2013, he was facing up to 35 years in prison and a one-million dollar fine for 13 felony counts related to violating copyright laws. Today the NY Southern District Court ordered the shut down of a website (Sci-Hub) run by Alexandra Elbakyan, a neuroscience graduate student from Kazakhstan, for violations of copyright laws. (The Sci-Hub server is believed to be in Russia and isn’t shutting down.) As leaders in the open access movement, the actions of Swartz and Elbakyan were about making scientific publications available for free.

Their solution is one approach to the problem of access to science. There is a related access problem that citizen science can help tackle.

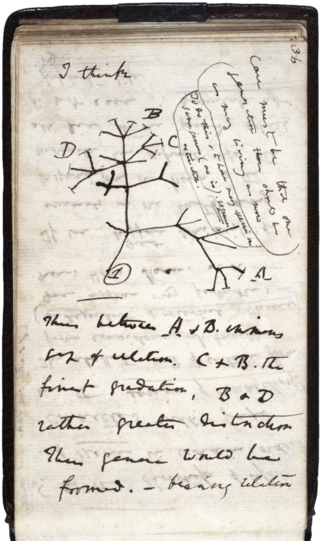

Scientists communicate with each other through the peer-reviewed literature. One discovery sparks a new study that leads to another discovery and helps make sense of past discoveries, and so on, as our collective understanding grows. Because the exchange of ideas, insights, methodologies, and discoveries is critical to scientific progress, scientists must not be isolated from one another. Yet, scientists in less affluent parts of the world can feel the most isolated, often from not having enough financial resources to access the scientific literature.

The open access movement challenges the financial structure of the current publishing model in science, but there is more to access than freely getting scientific papers in hand (or on the screen). Access is more than viewing the words. Access also involves turning words into meaningful information. There are several ways that citizen science projects that focus on words contribute to various and sundry ways of opening access to science.

First, some citizen science efforts help researchers make sense of the reams of literature.

Scientific papers are published at a rate of two every minute. There are 47 million papers on Sci-Hub. One million new articles appear on PubMed every year. No individual can keep up with the current rate of discoveries. No individual can read it all. According to Andrew Su at the Scripps Research Institute, the scientific literature is itself Big Data. It requires humans and computers working together to make meaning of it all.

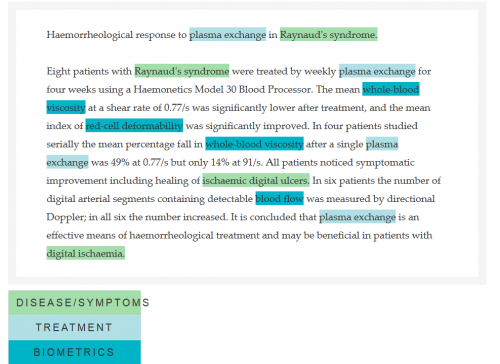

Su’s citizen science project, Mark2Cure, calls upon volunteers to tag words that represent specific concepts in the biomedical literature. From the work of crowds of people tagging the names of diseases, genes, and drugs, Su and his team can build concept maps and identify new relationships otherwise hidden. You don’t have to understand the scientific literature or the jargon to participate. You just have to read English well enough to pick out the names of diseases, even without being familiar with the disease. Mark2Cure focuses on rare genetic diseases, currently one called NGLY1 deficiency. Biomedical researchers can sequence the entire genome of those with rare diseases. They can identify the genetic mutation causing the disease. But without background knowledge about the gene, there is no obvious treatment. Mark2Cure will help researchers spot connections and home in sooner on promising research directions that would go otherwise unseen in the mounds of literature.

Second, citizen science transcription projects make historic museum and herbarium specimens accessible to researchers globally. For example, Zooniverse hosts Notes from Nature, an online platform to transcribe specimen labels. With about two billion specimens in natural history museums around the world, these irreplaceable specimens hold valuable and unanticipated insights. With transcription projects, citizen science has fuzzy boundary with crowdsourcing in humanities, such as the Smithsonian Transcription Center which focuses on digitizing a wide range of early print and handwritten diaries, ledgers, logbooks, photo albums, field notes and other documents that only the human mind can decipher. These projects mobilize information from the past and make it accessible to everyone via the Internet.

Third, citizen scientists participate in scientific discovery. That’s public access not to the fruits of science, but right to its roots, access to the scientific process. In some cases, like projects in GamesWithWords.org, participation is partly as a human subject of the research. Linguists pursue a variety of research topics related to language and citizen science can be a fun way for people to participate in studies, such as from investigating the ever-evolving rules of grammar with Verb Corner to experiments on distractibility with Ignore That!

On the next #CitSciChat, we’ll discuss citizen science related to tagging, transcribing, and having fun with words. Join us on Wednesday Feb 24th at 2pm ET (7pm GMT; Thursday 8am NZDT) on Twitter at the hashtag #CitSciChat (or follow steam here: www.carencooper.com/#CitSciChat. I’m the founder and moderator of #CitSciChat (@CoopSciScoop), sponsored by SciStarter (@SciStarter). Guest panelists this week include:

Joshua Hartshorne (@jkhartshorne) from GamesWithWords.org & The Language Learning Lab at Boston College

Meghan Ferriter (@meghaninMotion) of the Smithsonian Transcription Center (@TranscribeSI)

Michael Denslow (@NfromN) from Notes from Nature

Andrew Su (@Mark2Cure) from Mark2Cure

Sioban Leachman (@SiobhanLeachman), citizen scientist #volunpeer extraordinaire

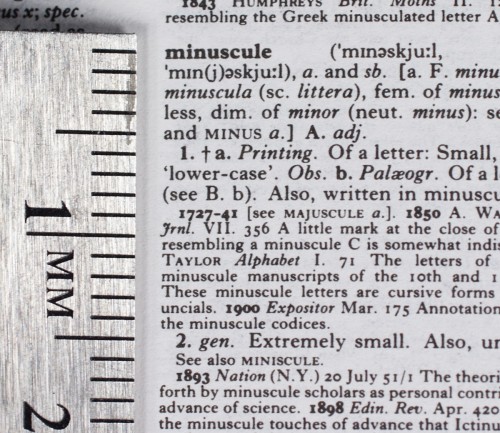

One of the key literacy tools, the dictionary, or specifically the Oxford English Dictionary, was created by crowdsourcing words from the general public. Interestingly the most prolific contributor of words to the dictionary was WC Minor, an army surgeon and veteran of the US Civil War, who did his citizen philology from a London insane asylum.

You don’t need to be crazy, or a devout pirate bravely attempting to abolish copyright, in order to help make science more accessible. There are ways the publication system is broken, and many who support the open access notion don’t want to openly endorse illegal methods. With citizen science, researchers and the public collaborate to mobilize new papers, specimens, and historic documents for collective use. As Swartz said, “The library world is set up on this model where the library is a physical building and has a number of books and servers a geographic community… What if there was a library which held every book? Not every book on sale, or every important book, or even every book in English, but simply every book – a key part of our planet’s cultural legacy.” And every specimen, ledger, logbook, etc. And all tagged and searchable.

Citizen science projects with words mobilize information into knowledge. Citizen science provides people with access to the knowledge-producing system of science.

Word.

This article was written by Caren Cooper and published in blogs.plos.org

http://blogs.plos.org/citizensci/2016/02/23/coops-scoop-opening-access-with-citizen-science-in-a-word/

Caren is an Associate Professor at North Carolina State University, Chancellor’s Faculty Excellence Program in Leadership in Public Science, as well as the assistant director of the Biodiversity Research Lab at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. She is an avian ecologist and relies on citizen science to help communities use birds as indicators of environmental health. She hosts monthly chat sessions about citizen science on Twitter, and author of Citizen Science: How Ordinary People Are Changing the Face of Discovery. Follow her at @CoopSciScoop